Latest News

Sustainable Stainless Steel in Engineering and Construction

20 April 2025

Abstract

Stainless steel is an environmentally friendly metal widely used in engineering and construction. Stainless steels are used in energy generation, to provide clean air, in water conservation, to contain hazardous chemicals, and to limit metal contamination in the environment. If the correct stainless steel and surface finish are selected the metal will remain functional over the service life of an engineering structure, possibly for more than a hundred years.

Many of the characteristics that determine whether an engineering material is green are related to its corrosion resistance. Stainless steels have high embodied energy but a very low corrosion rate as well as high salvage value, which ensures a good overall embodied energy during a long service life. The long service life of stainless steel also maximises the durability of other engineering materials by preventing premature failure of systems designed with stone, masonry and timber.

This paper outlines how to achieve a long trouble-free service life using stainless steel by applying best industry practices and good fabrication techniques. Applications of stainless steels will illustrate why this metal is a truly sustainable engineering material to employ in engineering and construction.

Introduction

Stainless steel is a material with attractive appearance, excellent corrosion resistance, good mechanical properties, low maintenance requirements and long life. These properties are valued by design engineers and as a result, stainless steel is finding increasing use in a wide range of applications in engineering structures. Over the past 50 years, the use of stainless steel has grown at an average annual rate of almost 6%. Presently about 20 million tonnes of stainless steel are used each year around the world and about 12% of this is used in the field of architecture, building and construction. In Asia, the percentage is even higher – about 33% of all stainless steel is used in these fields. Some uses are very evident, such as building façades, shop fronts, column wraps (Figure 1), lift doors, hand rails and a wide range of street furniture (Figure 2). Other more sustainable applications, such as reinforcing bar and wall ties, are structural in nature.

The vast majority of applications are successful, which is the reason for the rapid rate of growth in stainless steel usage. Occasionally some applications are not so successful, but it is very rare for stainless steel to fail structurally. However, there are an unnecessary number of cases where the surface of stainless steel turns brown in colour – it develops a thin layer of rust called Tea Staining and this is one way in which stainless steel ‘fails’.

Meeting modern demands – sustainability

Like all major industries around the world, the engineering and construction field is highly competitive. Engineers and owners are constantly striving to create engineering structures which:

- Are durable but deliver improved value for money at the time of construction.

- Establish a competitive advantage in the market through some unique design or image.

- Minimise maintenance and refurbishment costs over the life of the structure.

- Are recognised as green structures by reducing demands on the environment during manufacture and over the life of the structure.

- Have an acceptable level of embodied energy – the energy consumed in the production of the material right through to its end use.

Stainless steel is uniquely placed to meet these needs because of its inherent properties, which include:

- Quality appearance and image.

- Wide range of available surface finishes allowing customised designs.

- Excellent corrosion resistance offered by a range of stainless steel grades.

- No necessity to be painted – eliminating a maintenance cost and any environmental emission (i.e. no VOC’s as in paint).

- Excellent fabrication characteristics – good formability and weldability.

- No bio toxic runoff from roofs or claddings

- Potential for high strength in structural applications.

- Low maintenance requirements (but not zero maintenance).

- Durable with realistic expectation of a long life

- High embodied energy, but 100% recyclable at end of service life.

One of the most famous buildings in the world is the Empire State Building in New York (Figure 1). It was constructed over 70 years ago and it demonstrates many of the attractive characteristics of stainless steel that are listed above.

To enjoy these benefits, it is important to understand the characteristics of stainless steel. Like all engineering materials, it must be correctly specified, designed, fabricated, installed, and maintained.

Figure1. Left: Empire State Building, New York. Built in 1931; 382m high with 85 floors of office space. It was the world’s tallest building for 41 years. Right: Over 300 tonnes of type 302 stainless steel was used as window surrounds and decoration.

What is stainless steel?

When carbon steel is exposed to a corrosive environment, such as a humid atmosphere, it forms an iron oxide on the surface which is commonly called ‘rust’. This iron oxide film is not protective and if the carbon steel is exposed long enough, it will entirely change to rust. If enough chromium is added to the carbon steel then the nature of the surface oxide changes: a continuous chromium-rich oxide film forms which is protective and prevents further corrosion of the metal. The minimum amount of chromium (Cr) required to do this is about 11 % and this is the figure which is most commonly used to define a stainless steel; it is the passive chromium oxide film which gives stainless steel its corrosion resistant properties.

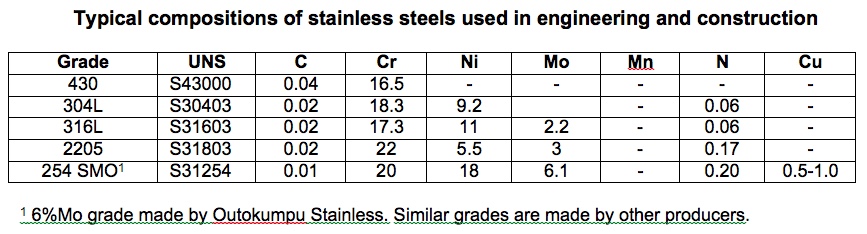

Such an iron-chromium alloy is a ferritic stainless steel, named after the crystal structure of these steels which is ferrite. The formability and weldability of stainless steel can be improved if the crystal structure is changed from ferrite to austenite and the most common way of doing this is by adding nickel to form the 300 series nickel- chromium stainless steels. The most common such alloy is called type 304. Molybdenum may be added to further improve resistance to corrosion, particularly when chlorides are present such as in marine atmospheres and when there is air pollution present. Type 316 stainless steel contains at least 2% molybdenum and this element distinguishes it from type 304, which contains no deliberately added molybdenum. Table 1 gives the compositions of some stainless steels used in engineering and construction.

Table 1

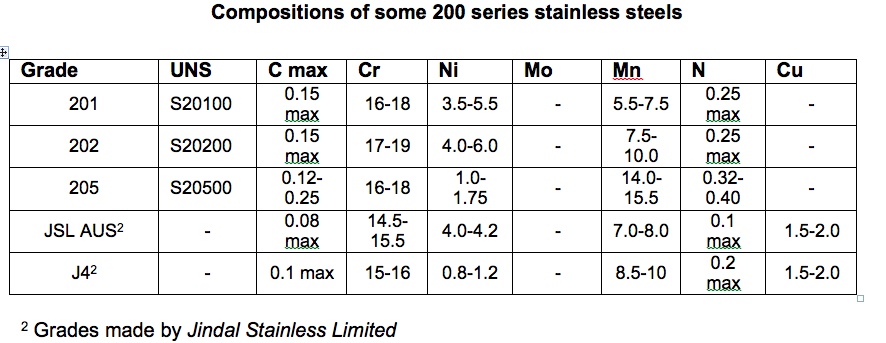

Nickel is a versatile and valuable alloying element, but it is expensive, and its price varies depending upon supply and demand. At present the nickel price is relatively high and because of this there is interest in other alloying elements which can replace some of the nickel. Manganese is useful in this regard. It is not a strong austenite former, but it allows higher levels of nitrogen to be added to the stainless steel and nitrogen is a strong austenite former. Copper also helps to form austenite and there are now available on the market several austenitic stainless steels which use some combination of nickel, manganese, copper, and nitrogen to ensure that the crystal structure is entirely austenite. It is common in the marketplace to refer to high manganese alloys as 200 series stainless steels, but this term should only be used for those alloys which have an AISI 200 series number, such as types 201 and 202. Many of the stainless steels of this grade that are being offered are proprietary grades and do not have a 200 series number.

200 series stainless steels were used in the United States in the early 1950s when there was a period of nickel shortage during the Korean War. Since then, 200 series alloys have occupied niche markets in developed countries, mainly based on their relatively high strength. These resulted in their use for nuts and bolts, drive shafts, valve stems, and various applications requiring galling and wear resistance. In these applications it is their mechanical properties which are attractive – they have not been developed with lower cost as the main objective. The country where 200 series stainless steels have achieved greatest use is India where particular grades were developed to reduce the cost of stainless steel for applications such as basic kitchen utensils. Over the past few years, the lower cost stainless steels have become increasingly common. Table 2 gives the compositions of some 200 series stainless steels.

Table 2.

Technical issues to be addressed

The performance of a stainless steel engineering structure depends upon a combination of the following factors:

- Environment

- Design

- Grade selection

- Surface finish

- Good fabrication and installation practices

- Maintenance

For a stainless steel application to be successful it is essential that each of these factors is considered when the project is at an early stage. Some of the important points associated with each of these factors’ areas follow.

Environment

The environment is fundamentally important in determining corrosion performance. Stainless steel cannot corrode by itself; it is often contamination in the environment that causes corrosion, so it is important to understand the grade and level of contaminants which are present. Chlorides are the most common aggressive contaminant and chlorides are present in marine atmospheres. Air pollution from sources such as industry and automobiles can also accelerate corrosion. The most aggressive environments are:

- outdoors in marine locations.

- in the presence of air pollution (e.g. Sulphur oxides).

- in areas not easily washed by rain.

Strong economic development in some areas of the world has resulted in rapid increases in air pollutant emissions and this is expected to continue over coming years. Sulphur oxide levels are high, which can result in acid rain, and particulates such as carbon “soot” are produced from burning coal and other sources. Even in inland cities this is a corrosive mix, but in coastal cities where air pollution is combined with marine chlorides, severe demands are placed upon materials used for structural applications.

When assessing the environment, it is important to learn from the experience of others. Stainless steel structures may already exist nearby. If not, they can probably be identified in similar environments at other locations and a lot can be learnt from studying their performance.

Engineering design

The following guidelines will help to avoid conditions which can lead to corrosion, and will also assist in keeping the structure clean:

- Use simple shapes which do not collect dirt or moisture and are easily cleaned.

- Avoid crevices where water and contamination can collect.

- Provide adequate drainage on flat surfaces to avoid ponding of contaminated water on stainless steel surfaces – called drain away design.

- Use smooth finishes that are less likely to collect dirt and are more easily cleaned.

- If the finish has a grain, orient it vertically for better rain washing and drainage.

- Do not design sheltered areas that cannot be washed by rain. If such areas cannot be avoided, use a more corrosion resistant stainless steel or plan for regular cleaning in those areas.

- Provide a window washing system or other means of access for cleaning exterior stainless steel.

- Avoid unfavorable dissimilar metal couples – galvanic corrosion can occur.

Do not place dissimilar metals in contact in wet areas or ensure that the galvanic couples are favorable. Stainless steel is cathodic (noble) relative to most other common building metals, so other metals can corrode (anodic) when in contact with it. This can be avoided by ensuring that different metals are not in contact, or by ensuring the surface area of stainless steel is small compared with the surface area of the other metal. It is for this reason that stainless steel screws, rivets and bolts are often used to fix aluminum or galvanized steel. However, rapid corrosion could occur if fasteners in those other metals were used to fix stainless steel.

Types 304 and 316 stainless steel sheet metal can be rolled to make tight bends due to the excellent ductility of austenitic stainless steels; this is a desirable property of stainless steels for architectural claddings and roofing.

Stainless steel grade selection

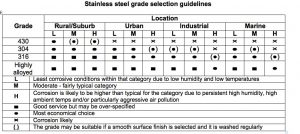

For indoor applications in low corrosion environments, ferritic type 430 (and other new ferritic grades) may be suitable. But most engineering applications are met using types 304 and 316 stainless steel. Type 304 is suitable for most indoor applications and for a wide range of less demanding external applications. Where the external environment is more corrosive, type 316 is generally chosen. Such aggressive environments usually involve the presence of chlorides, for example in marine atmospheres, or Sulphur oxides most commonly from automotive exhausts or industrial air emissions.

For severe marine environments and areas which suffer from heavy industrial pollution type 316 may not be satisfactory. It may be necessary to use a more highly alloyed stainless steel such as type 904L, duplex grade 2205, or even a super austenitic 6%Mo grade.

Type 304 is the most common grade used for engineering and construction. 304 generally works well and this is assisted by the fact that it is commonly used with a bright, very smooth finish such as a BA or mirror polish. If a rougher polish such as the No.4 finish was used, it would be more subject to surface corrosion because deposits would accumulate on the polished surface more easily. However, even bright finished type 304 is not suitable for aggressive atmospheres unless it is frequently washed to remove surface contamination. Type 316 is a much more suitable grade for such an environment. Even so, the surface finish and cleaning frequency must be carefully considered at the time of construction.

Table 3 is a useful guide to the selection of stainless steels for engineering and construction.

Table 3.

As previously noted, there is a lot of interest at present in the use of cheaper 200 series stainless steels to replace the higher-nickel type 304. This can be appropriate in some situations, and indoor furniture may be an example. However, it appears that 200 series stainless steels are sometimes being used in applications where they do not have sufficient corrosion resistance, such as exterior use in humid, polluted, and marine atmospheres. This is a concern to the entire industry since any stainless steel failure creates negative attitudes towards all stainless steel as an engineering material.

This situation is further complicated by several other aspects:

- Some people may not be aware that they were buying a lower alloy stainless steel (rather than type 304) since they were being offered ‘cheaper stainless steel’ without Material Certificates being made available. Therefore, request a Material (or Heat) Certificate for the alloy from the supplier at an early stage.

- It is not uncommon for incorrect names to be used with the 200 series stainless steels. 200 series alloys and ferritic stainless steels should not be considered as inferior to 300 series grades, but they are different. They have different mechanical properties such as strength and elongation and they have different corrosion resistance. Like all materials, sometimes these properties are suitable for a application and sometimes they are not.

- One problem in providing advice about the suitability of various grades of stainless steels is that they are often proprietary alloys about which there is relatively little data, experience and research results compared with grades such as types 304 and 316 which are covered by a variety of National and International Standards, and for which there are many decades of field experience.

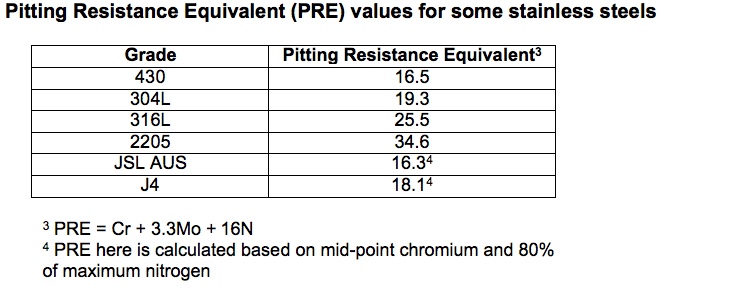

The tea staining problem that can form on the surface of a stainless steel in aggressive atmospheres is a form of fine surface pitting corrosion. An indication of the resistance of a stainless steel to this grade of pitting corrosion attack is given by the Pitting Resistance Equivalent, PRE:

PRE = %Cr + 3.3 %Mo + 16 %N

Table 4 gives the PRE values for types 430, 304 and 316 stainless steel as well as for duplex 2205 stainless steel. Also included are two typical 200 series stainless steels; both have PRE values less than that of type 304.

Good advice to users of stainless steel in engineering applications is to be sure that you know what you are buying and ensure that you have reliable, quantitative data on the performance of that material in an application such as you are planning.

Table 4.

Surface finish

The best guideline is that the smoother the surface of the stainless steel the better will be its corrosion performance. With smooth surfaces it is more difficult for contamination to adhere to the surface and to build up; it is also easier for rainwater or manual cleaning to remove any aggressive deposits that can cause tea staining.

Smooth surfaces such as 2B, BA and mirror polish have better corrosion performance than rougher polished finishes such as a no.4 finish. As a general guide, corrosion resistance of stainless steel improves from left to right in the following sequence:

No.1 ‹ 2D ‹ No.4 ‹ 2B ‹ BA ‹ No.8 (mirror finish)

To achieve good corrosion resistance for marine applications, stainless steel must have a transverse surface roughness smoother than Ra 0.5 mm and a clean-cut surface finish. Smooth, polished finishes on stainless steel are quite reflective and sometimes it is preferable to have a finish with lower reflectivity, because a highly reflective finish may provide a light reflection hazard. In this case, a variety of textured designs are available which use a smooth substrate such as 2B or BA. They are easy to wash because they are smooth at a micro level and create much less glare particularly in sunlight because they are rough at a macro level.

Good fabrication and installation practices

The fabrication of stainless steel is not difficult, but it is different from the fabrication of mild steel. Some of the main considerations are:

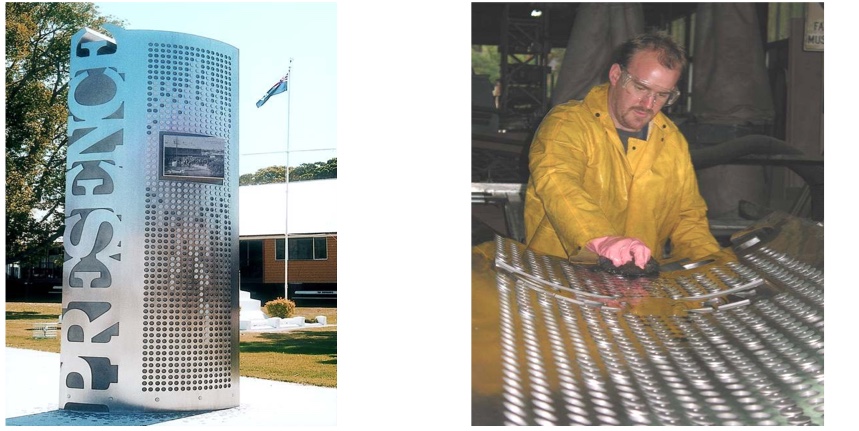

- Remove heat tint (discoloration) produced during stainless steel welding, since the layer immediately beneath the discoloration is depleted in chromium and therefore has inferior corrosion resistance. Heat tint can be removed chemically by pickling (Figure 2) or electropolishing, or mechanically by fine grinding.

- Ensure that no particles of iron (steel) are embedded in the surface of the stainless steel. This can occur, for example, when stainless steel is cut using a shear blade which has been used on carbon steel, or when stainless steel is ground using a grinding wheel which has been used on carbon steel and is therefore contaminated with steel particles. Do not process stainless steel using equipment which has been contaminated in any way with carbon steel (Figure 3).

- Ensure that the surface of stainless steel is not contaminated during transportation or storage on site. This can happen if fabrications come into contact with steel chains or wire slings, or if weld spatter or grinding particles from site work deposit onto the surface of stainless steel. For these reasons, it is wise to protect the surface of stainless steel at all stages of transportation, storage, and installation.

- Make sure that masonry cleaning chemicals do not contact the surface of stainless steel. Such chemicals sometimes contain hydrochloric acid which is very corrosive.

- After installation, make sure that the surface is thoroughly cleaned since the best corrosion performance is achieved with a clean, smooth surface. Any plastic film which has been used to protect the surface of the stainless steel should be removed and care taken to ensure that no adhesive residues are left on the surface.

Figure 2. Left: Type 316 stainless steel memorial. It has been finished with a vertical No.4 polish finish. Right: To ensure good corrosion performance, welds are pickled with mixed acids and the entire surface of the fabrication is chemically cleaned and passivated with nitric acid.

Figure 3. Corrosion of steel (iron) particles embedded in type 304 stainless steel roof sheeting. The cold forming rolls had previously been used with carbon steel sheet and were contaminated with particles of steel.

Maintenance

Stainless steel is a low maintenance material, but it is not maintenance-free. If the original luster of the stainless steel is to be retained, then it is necessary to carry out periodic cleaning. The cleaning frequency required varies depending on:

- The severity of the environment: rural, inland environments contain less contaminants such as chlorides and so create less need for cleaning than marine or industrial environments.

- The climate: there is less need for manual cleaning if the stainless steel structure is located in a region where there is regular heavy rainfall to wash off contaminants. The worst situation is where there is high humidity and high ambient temperature, e.g. only light rain, or fog. Because contamination is not washed off, the stainless steel surface is kept damp, which can create a corrosive electrolyte (a salt film).

- Position of the stainless steel on the structure: building elements that are washed regularly by rainwater require less frequent manual cleaning than areas that are exterior but protected from rain washing, such as under the eaves of buildings. The Chrysler Building in New York is a good example – since construction in 1930, it has been manually cleaned only twice (1961 and 1995), yet it is in very good condition because the 302 grade stainless steel cladding has a smooth surface finish and is regularly washed by rain.

A general but useful guide is that external stainless steel should be cleaned at the same frequency as window glass, and in a similar fashion – with detergent or ammonia in water, washed off with clean water. It should be noted, however, that there are many successful stainless steel structures which are not cleaned frequently. The most appropriate cleaning regime to be adopted in each case depends upon the environment, design, grade and finish, as well as on the owner’s aesthetic expectations.

Inter-relationship of the above factors

All the factors which have been discussed, from design through to maintenance, contribute to the performance of stainless steel in an inter-related manner. For example, if a very smooth surface finish is used then it is possible to specify a less highly alloyed grade of stainless steel and still achieve the same corrosion performance and service life. Similarly, if regular cleaning is carried out, satisfactory performance can be achieved with a lower grade of stainless steel and a slightly rougher surface finish. A good example is stainless steel handrails that are regularly cleaned by people’s hands during use, which diminishes the likelihood of surface corrosion occurring.

Conclusions

- Stainless steel is one of the most sustainable materials used in engineering and construction.

- Stainless steel has been used in such applications for over 80 years and there exists a great deal of knowledge about its performance.

- The guidelines given have been developed based on experience and provided that they are followed stainless steel structures will be durable and cost effective.

Bibliography

(1) Guidelines for the welded fabrication of nickel-containing stainless steels for corrosion resistant services (Nickel Institute No.11007)

(2) Stainless steel in architecture, building and construction: Guidelines for roofs, floors, and handrails (NI No.11013)

(3) Stainless steel in architecture, building and construction: Guidelines for maintenance and cleaning (NI No.11014)

(4) Stainless steel in architecture, building and construction: Guidelines for building exteriors (NI No.11015)

(5) Timeless Stainless Architecture (NI No.11023)

(6) Stainless Steels in Architecture, Building and Construction: Guidelines for Corrosion Prevention (NI No.11024)

(7) Fabricating stainless steels for the water industry (NI No.11026)

(8) Design manual for structural stainless steel (NI No.12011)

(9) Successful use of stainless steel building materials (NI No.12013)

(10) Which stainless steel should be specified for exterior applications? (International Molybdenum Association; www.imoa.info).

(11) Code of Practice for the Fabrication of Stainless Steel Plant and Equipment, NZSSDA, 2001.

Acknowledgement

This paper was presented at the 4th New Zealand Metals Industry Conference, 29-31 October 2008, Sky City Convention Centre, Auckland. The 4th NZ Metals Industry Conference was organised by HERA: www.hera.org.nz.